대황목단피탕의 항산화 및 항염증 효과 평가

Antioxidative and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Daehwangmokdanphee-tang

Article information

Trans Abstract

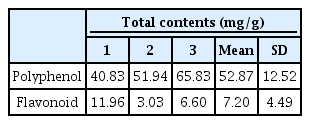

This study was conducted to investigate antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of Daehwangmokdanphee-tang (DHMDPT). The antioxidant activity was evaluated the total polyphenol contents and total flavonoid contents. Additionally we measured the ABTS radical scavenging activity, superoxide dismutase (SOD)-like activity and electron-donating ability with DHMDPT. In addition, inhibition of NO production in RAW 264.7 cells induced by LPS was evaluated to investigate the anti-inflammatory effect. The results of total polyphenol contents, total flavonoid contents was 52.87±12.52 mg/g and 7.20±4.49 mg/g in DHMDPT. Antioxidant activity results of DHMDPT through ABTS radical scavenging activity, superoxide dismutase (SOD)-like activity, and electron-donating ability are highly active in a dose-dependent showed high activity. The cell toxicity of DHMDPT was evaluated using the RAW 264.7 cells. LPS-induced inhibition of NO secretion was increased in DHMDPT in a dose-dependent manner. This result indicates that DHMDPT might have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in vitro assay, and can be developed as a cosmetic material in the future.

I. 서 론

최근 환경오염 및 화학물질 등에 대한 불안과 건강에 대한 소비자의 관심이 증가됨에 따라 건강한 아름다움에 대한 요구가 증가하고 있다(Jae & Kim, 2015). 이에 따라 소비자들은 피부에 직접 도포하여 인체에 흡수되는 화장품에 대한 관심이 높아지고 있으며, 많은 연구자들은 이러한 소비자의 욕구에 따라 안전한 화장품 원료로 알려져 있는 식물유래 천연물에 대해 활발하게 연구를 수행하고 있다(Lee & Ryu, 2019). 특히 기능성 화장품개발을 위한 연구에서는 식물유래 천연물의 항산화, 항염, 항균, 미백, 주름개선, 항노화 등과 같은 생리활성을 일으키는 원료물질의 탐색이 최우선 과제이다(Cho, 2011).

인체에서 발생되는 산화적 스트레스는 생체분자에서 과도한 산화적 반응을 일으키게 되고 그 결과 줄기세포의 감소, 세포 노화 등의 부정적 결과를 초래할 뿐만 아니라 피부 노화의 원인이 되기도 한다(Schieber & Chandel, 2014; Kammeyer & Luiten, 2015). 산화스트레스는 주로 hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide anion (O2-), hydroxyl radical (OH-) 등의 활성산소종(ROS)에 의해 발생하며, 이러한 활성산소종(ROS)의 증가는 피부의 화학적, 형태학적인 변화를 발생시켜 유발시켜 염증을 촉진시킨다(Thannickal & Fanburg, 2000; Zhou et al., 2003). 피부에서의 염증발생은 각종 호르몬, 사이토카인 등의 변형을 활성화하여 각종 질병을 유발하고 피부의 노화를 발생시킨다(Heo et al., 2008) 이와 같이 피부 노화는 산화적 스트레스 뿐만 아니라 염증 반응에 의해서도 촉진되며, 염증반응으로 인해 발생하는 피부 노화를 inflammageing이라고 한다. 염증을 의미하는 inflammageing는 inflammation과 ageing의 합성어로써 염증 반응과 관련되는 세포 신호전달과 염증 반응으로 생성되는 활성 산소가 세포노화에 작용을 한다는 것을 의미한다(Cevenini et al., 2013).

염증(inflammation)은 우리의 생체를 보호하기 위한 방어 기전의 하나로 virus나 bacteria와 같은 병원균의 침입에 대한 면역세포 보호반응이다(Lee & Kim, 2021; Choi, 2022). 염증반응에서 중요한 역할을 하는 대식세포 중 Lipopolysaccharide(LPS)로 활성화시킨 RAW 264.7 세포는 항염효과를 탐색하기 위해 가장 널리 사용되고 있다. RAW 264.7 세포가 염증유발물질 LPS의 자극받으면 cyclooxygenase-2(COX-2), inducible nitric oxide synthase(iNOS) 및 cytokine과 같은 염증인자들의 분비를 촉진시키고 leukotriene, prostaglandin 및 nitric oxide(NO)를 생성시켜 염증반응을 일으킨다(Ko et al., 2017).

인체는 산화적 스트레스로부터 발생되는 염증으로부터 초과산화물 불균등화 효소(SOD), 글루타티온 과산화효소(GPx), 글루타치온 환원 효소, 카탈라제와 같은 효소 산화방지제와 글루타티온(GSH), 비타민C, 비타민D와 같은 비효소계 항산화제를 분비하여 생체의 질환, 비만, 피부노화 등으로부터 우리 몸을 보호한다(Reuter et al., 2010). 이처럼 산화적 스트레스와 염증 반응은 밀접한 연관성을 가지고 있으며, 산화적 스트레스를 감소시키는 항산화 물질은 염증반응 또한 감소시킬 수 있으므로 최근 우리가 관심을 가지는 만성적 질환들과 생체 및 피부 노화를 효과적으로 억제하기 위해서 항산화 물질의 개발은 매우 중요한 과제이다(Kageyama & Waditee-Sirisattha, 2019).

대황목단피탕은 소장이나 대장 등에 생긴 종기 치료에 사용되고(Lee, 2015) 혈행장애로 인한 병후에 널리 사용되는 한방 약재로서 동한(東漢)의 유명한 의사인 장중경(張仲景)이 저술한 상한잡병론(傷寒雜炳論)의 잡병 부분에 해당하는 금궤요락(金匱要略)에 처음 수록된 이후로 여러 문헌에 기재되어 있다(Park et al., 2005; Ahn et al., 2006). 대황목단피탕은 대황(Rhei Rhizoma), 목단피(Moutan Cortex), 망초(Natrii sulfas), 도인(Persicae Semen), 동과자(Beninecasae Semen)로 구성되어 있으며 이들 각각의 물질이 항산화 및 염증억제에 효과가 있다는 문헌(Han et al., 2015; Park, 2020; Kim et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2022; Park & Lee, 2020)이 있으나 특히 화장품 소재로써 대황목단피탕에 관한 연구 및 항산화와 항염효과에 관한 과학적 근거자료는 거의 전무한 실정이다(Lee, 2015).

본 연구에서는 다양한 효능이 있다고 알려진 대황목단피탕을 통해 항산화 평가와 RAW 264.7 cell을 이용한 항염증 효과를 탐색하여 추후 피부노화 억제를 위한 화장품 소재로서의 응용가능성을 확인하고자 하였다.

II. 재료 및 방법

1. 시약 및 기기

항산화 평가의 대조군 사용된 ascorbic acid, tannic acid, quercetin, 2,2'-azino-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), folin&ciocalteu's phenol reagent, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid(10 mM EDTA), pyrogallol와 tris(hydroxymethyl)-amino-methane(50 mM tris)은 Sigma-Aldrich사(St. Louis, U.S.A.)의 제품을 사용하였다. 그리고 penicillin/streptomycin, fetal bovine serum, dulbecco's modified Eagles Medium(DMEM) 등은 Lonza Company(Walkersville, U.S.A.)의 제품을 사용하였다. 그 외는 실험실 내 일반 시약을 이용하였다. 실험에 사용한 실험기기로는 전자저울(XT220A, Precisa, Dietikon, Swiss), spectrophotometer(Epoch, Bio Tek, Winooski, U.S.A.), CO2 incubator(MCO-18AC, panasonic, osaka, Japan) 그 외 기기들은 일반적인 실험실 기기를 사용하였다.

2. 시험물질

본 시험에서 실험물질로 사용한 대황목단피탕의 구성은 Table 1과 같다. 대황목단피탕의 구성원료는 경상북도 영천시 소재의 (주)옴니허브에서 구입하여, 증류수로 세척하고 음건 후 Table 1의 구성비로 혼합하여 사용하였다. 이후 시료 중량대비 3배의 70℃ 증류수에 1시간동안 pH 7.0 조건에서 추출하여 열수추출을 실시하였다. 시료는 상온에서 냉각, 여과의 과정을 거쳐 동결건조를 진행한 후 만들어진 파우더를 -20℃에서 보관하며 실험에 사용하였다.

3. 항산화 활성평가

1) Total polyphenol contents

Folin and Denis법(Folin & Denis, 1912)에 의거하여 총 폴리페놀 함량을 측정하였다. 멸균증류수 7.5 ml와 시험물질 1 ml을 혼합한 후 Folin-reagent 0.5 ml을 가하여 균질하게 섞어 3분 간 반응시켰다. 그리고 760 nm 파장에서 흡광도 측정을 위해 Na2CO3 포화용액 1 ml 첨가하여 1시간 반응시켰다. 표준물질로 Tannic acid를 사용하였으며 표준곡선을 이용하여 총 폴리페놀의 양을 환산하였다.

2) Total flavonoid contents

대황목단피탕의 총 플라보노이드 함량은 다음과 같은 방법으로 측정하였다. 시험물질 0.5 ml, 10 % Aluminum nitrate 0.1 ml, 1 M Potassium acetate 0.1 ml, Ethanol 1.5 ml, 멸균증류수 2.8 ml을 모두 혼합하여 차광시킨 다음 40분간 상온에서 반응시킨다. 공시험군은 멸균증류수를 사용하여 실험을 진행하였으며, 반응 종료 후 용액을 415 nm 파장에서 흡광도측정을 하였다. 표준물질로 quercetin를 사용하였으며 표준곡선을 이용하여 총 폴리페놀의 양을 환산하였다.

3) ABTS+ radical scavenging activity

대황목단피탕의 ABTS 라디칼 소거활성율 측정은 ABTS+ cationdecolorization assay에 의해 시행하였다(Re et al., 1999). ABTS 용액은 실온에서 2.4 mM potassium persulfate와 7 mM 2,2-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)를 혼합 후 차광하여 실온상태에서 12시간 동안 반응시켰다. 12시간 반응 후 형성된 ABTS 용액은 ethanol을 이용하여 734 ㎚ 파장에서 흡광도 값이 0.7(±0.02)이 되도록 희석하였다. 농도별로 희석 된 대황목단피탕 0.1 ml과 희석된 ABTS 용액 0.1 ml을 혼합한 후 7분간 차광 상태로 방치하고 734 ㎚에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. ABTS+ 라디칼 소거활성율 측정은 다음의 식으로 산출하였다.

ABTS+ Scavenging activity (%) = [1 – (Asample/Acontrol)]×100

4) Superoxide domutase(SOD)-like activity

대황목단피탕의 SOD 유사활성은 Marklund-Marklund의 방 법(Marklund & Marklund, 1974)으로 측정하였다. 농도별로 희석 된 대황목단피탕 0.01 ml에 0.15 ml의 tris-HCl 완충용액(50 mM tris + 10 mM EDTA, pH 8.5)과 0.01 ml의 7.2 mM pyrogallol을 첨가하여 25°C에서 10분간 반응시켰다. 이후 반응을 정지시키기 위해서 0.05 ml 1N HCl을 첨가하였다. 반응액은 420 ㎚ 파장에서 흡광도를 측정하였으며, SOD 유사활성은 다음의 식을 이용하여 대황목단피탕을 포함한 시험 물질군과 대조군의 흡광도 감소비율을 나타내었다.

SOD-like activity activity (%) = [1 – (Asample/Acontrol)]×100

5) DPPH에 대한 electron-donating ability

전자공여능(electron-donating ability, EDA)에 의한 대황목단피탕의 항산화능 평가는 Blois법(Blois, 1958)으로 측정하였다. 농도별로 희석된 대황목단피탕 0.1 ml에 0.05 ml의 0.2 mM DPPH를 첨가하고 차광 상태에서 30분간 반응 후 517 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. 전자공여능은 다음의 식으로 대황목단피탕이 포함한 시험 물질군과 대조군의 흡광도 감소율을 나타내었다.

Electron-donating ability (%) = [1 – (Asample/Acontrol)]×100

4. RAW 264.7 cell을 이용한 항염 평가

1) 세포주 배양

실험에 사용된 마우스의 대식세포주 RAW 264.7 cell은 한국세포주은행(KCLB, Seoul, Korea)에서 분양받아 사용하였으며 10% fetal bovine serum와 1% penicillin-streptomycin을 첨가한 DMEM 배지를 사용하여 37℃, 5%, CO2 조건에서 배양하였다.

2) 세포독성

세포독성은 MTT assay를 활용하여 진행하였다. 96-well plate를 이용하여 RAW 264.7 cell을 1×105 cells/well로 나누어 37℃, 5% CO2 incubator를 이용하여 24시간 배양하였다. 이후 대황목단피탕을 농도별로 희석하여 200 μl씩 처치하고 동일한 조건에서 24시간 배양하였다. 배양 후 상층액을 제거하고 RAW 264.7 cell을 PBS를 이용하여 1회 washing 한 다음 0.5 mg/ml MTT solution을 200 μl씩 넣고 37℃, 5% CO₂incubator 에서 3시간 동안 반응시켰다. 상층액을 제거 후 DMSO를 이용하여 10분간 cell을 녹인 후 570 ㎚ 파장 흡광도를 측정하여 계산하였다.

3) LPS 처치에 따른 세포독성

96-well plate을 이용하여 RAW 264.7 cell을 1×105 cells/well로 나누고 37℃, 5% CO₂incubator를 이용하여 24시간 배양하였다. 이후 실온에서 대황목단피탕을 농도별로 LPS(0.1 μg/ml) 가 담긴 배지에 희석하고 처치 후 동일한 조건에서 24시간 배 양하였다. 배양 후 상층액을 제거하고 RAW 264.7 cell을 PBS를 이용하여 1회 washing 한 다음 0.5 mg/ml의 MTT solution을 200 μl씩 넣고 37℃, 5% CO2 incubator에서 3시간 동안 반응시켰다. 상층액을 제거 후 DMSO를 이용하여 10분간 cell을 녹인 후 570 ㎚ 파장의 흡광도를 측정하여 계산하였다.

4) NO 생성 저해

RAW 264.7 cell을 96-well plate에 1×105 cells/well로 나누고 37℃, 5% CO2 부란기에서 24시간 배양하고 대황목단피탕을 농도별로 LPS(0.1 μg/ml)가 담긴 배지에 희석하고 처치후 동일한 조건에서 24시간 배양하였다. 이후 상층액 100 μl를 제거하고 동량의 Griess 시약을 가해준 다음 540 nm 파장의 흡광도를 측정하였다.

5. 통계처리

통계처리는 SPSS 21.0 for windows(SPSS Inc., U.S.A.) 프로그램을 이용하였고 일원배치분산분석(one-way ANOVA)을 실시하였다. 각 그룹 사이의 차이 검정을 위해 Duncan's multiple range test를 이용하여 사후분석을 실시하였다. 본 연구의 통계학적인 유의성 수준은 p<0.05로 하였다.

III. 결과 및 고찰

1. Total polyphenol and flavonoid contents

산화적 스트레스로부터 페놀계 물질은 세포 DNA를 보호하고 손상을 억제한다고 알려져 있다(Hyun et al., 2015). 대황목단피탕의 총 폴리페놀과 총 플라보노이드의 함량은 Table 2와 같다. 총 폴리페놀 함량의 측정 결과는 52.87±12.52 mg/g이며, 총 플라보노이드 함량은 7.20±4.49 mg/g으로 나타났다. 흔히 알려져 있는 항산화 식물추출물의 폴리페놀과 플라보노이드의 함량은 대체적으로 높은편(Kang et al., 2015; Park et al., 2019)이며, 대황목단피탕에 포함되어 진 대황, 목단피는 불포화지방산을 포함하고 있으므로 다량의 폴리페놀과 플라보노이드가 검출 될 것으로 예상했으나 실험결과는 대황목단피탕의 폴리페놀과 플라보노이드의 함량이 다소 낮은 경향을 보였다. 불포화 지방산을 다량 포함하는 시료의 유효성분 추출 시 열을 가할 경우 추출물에 일부 변성의 발생 가능성이 있다(Jung et al., 2013). 본 실험에 사용된 대황목단피탕은 고온에서 장시간 열수추출을 진행한 것으로 대황목단피탕이 포함하는 불포화지방산으로 인해 추출 과정 중 일부가 변성한 것을 미루어 짐작해보며, 추후 다양한 추출조건에서 항산화능을 평가하는 연구를 진행하는 것이 필요하다고 보여진다.

2. ABTS+ radical scavenging activity

대황목단피탕의 ABTS+ radical 소거능의 결과는 Fig. 1과 같다. 본 실험은 ABTS 자유라디칼이 시험물질로부터 수소를 얻어 청색으로 탈색되는 원리로 항산화능을 측정하는 방법으로 항산화 측정에 많이 이용하는 실험법이다(Kim & Kim, 2016). Radical 소거능은 활성산소종와 유리기에 전자를 공여하는 능력으로 항산화 활성에 매우 중요한 지표로 작용한다(Re et al., 1999). 본 연구에서 사용된 모든 시험군에서 농도 의존적으로 ABTS+ radical 소거능이 증가하는 양상을 보였으며, 특히 가장 고농도인 1000 ㎍/ml에서는 75.9%의 높은 ABTS+ radical 소거능 활성을 확인하였다.

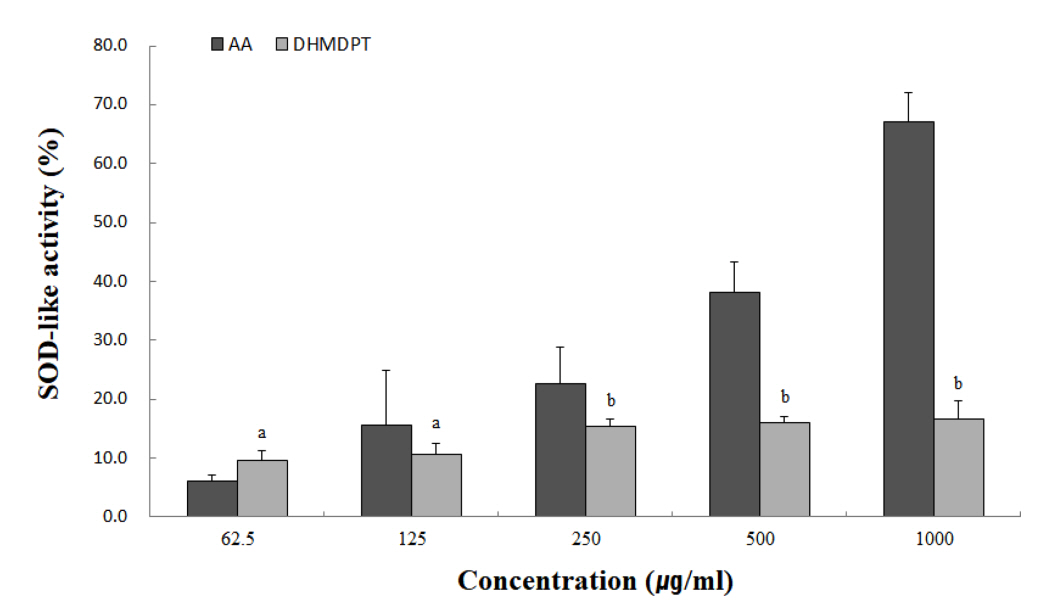

3. Superoxide domutase(SOD)-like activity

산소는 영양소를 통해 체내 에너지를 생산하는 생물학적인 시스템에 사용되지만 체내에서 생성되는 활성산소는 매우 불안정하여 반응성이 높아 산화 스트레스와 세포 손상을 일으킬 수 있다(Sies et al., 2005). Superoxide domutase(SOD)는 superoxide를 산소분자(O2)나 과산화수소(H2O2)로 변환시켜주는 역할하는 효소로서 산화적 손상으로부터 보호하는 phytochemical의 저분자 물질이다(Lee et al., 2016). 대황목단피탕의 SOD 유사 활성 결과는 Fig. 2와 같다. 본 결과는 과산화수소로 전환반응 시 촉매제로 사용되는 pyrogallol의 생성량을 측정한 것이며, 농도 의존적으로 모든 시료에서 SOD 유사활성이 증가하는 양상을 보였다. 이는 결과는 대황목단피탕이 pyrogallol의 산화적 손상을 방지하는것에 효과적인 SOD 유사활성물질을 포함한다고 보여진다.

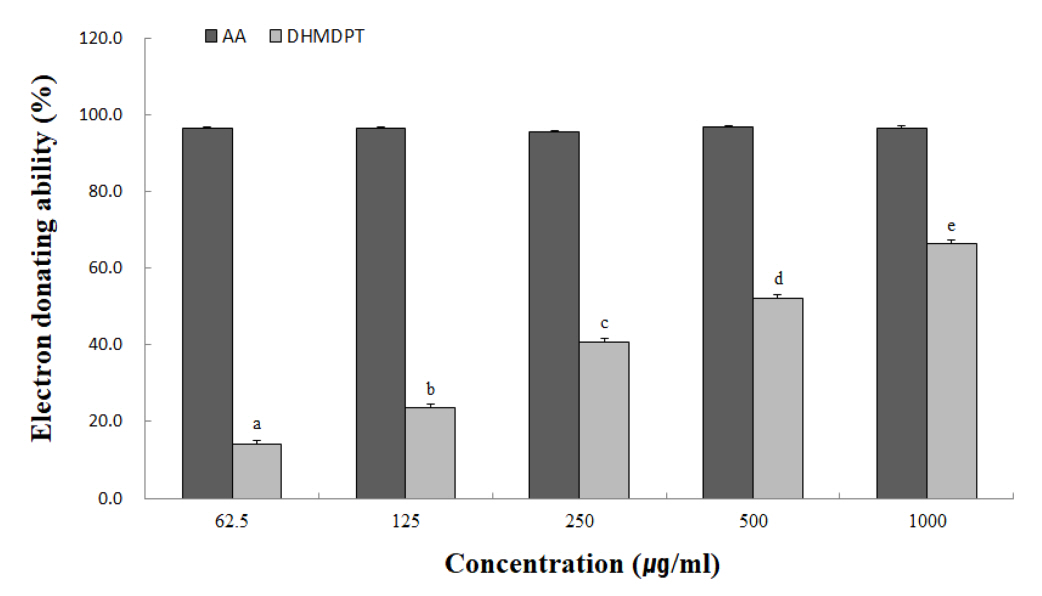

4. DPPH에 대한 electron-donating ability

다른 항산화 특정법에 비해 간단하면서 대량의 실험물질의 항산화 특정이 가능한 실험법인 DPPH에 대한 electron-donating ability은 항산화 물질 탐색을 위해 많이 활용되고 있다(Hyun et al., 2015). DPPH는 짙은 보라색을 띄고 있어 페놀성화합물, aromatic amine, ascorbic acid glutathione, cysteine 등에 의해 전자를 얻고 환원되었을 때 탈색정도를 측정하여 항산화력을 확인한다(Kim et al., 2016). 대황목단피탕의 전자공여능 결과는 Fig. 3과 같다. 농도의존적으로 모든 시료에서 전자공여능이 증가하는 양상을 보였다. 특히 저농도에서도 높은 항산화 활성을 보이는 것으로 확인되어 진다. 이는 화장품 소재 개발을 위한 아로니아 잎과 연복자 추출물의 전자공여능 연구결과와 동일 농도에서 거의 유사한 결과를 나타낸다(Lee & Ryu, 2018; Jang, 2021). 따라서 대황목단피탕은 화장품소재로서 가능성은 높은 것으로 사료된다.

5. 세포독성

대황목단피탕을 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200 ㎍/ml 농도로 RAW 264.7 cell에 처리했을 때 세포의 생존율은 Fig. 4와 같다. 시험 물질을 가장 고농도인 200 ㎍/ml으로 처리했을 때 RAW 264.7 cell의 세포생존율은 71.82 %을 나타내었다. 본 시험결과는 일반적인 한약재 추출물에서 100 μg/ml 미만의 농도에서 세포독성이 나타나지 않는 연구결과와 유사하다(Koo et al., 2021). 본 시험결과를 바탕으로 NO 억제율 측정 시 시험물질의 농도는 100 ㎍/ml 미만으로 설정하였다. 세포실험 시 일반적으로 80 % 이상의 세포 생존율을 나타내는 물질농도를 maximum permission level (MPL)로 지정했다. MPL 이하의 농도에서의 시험효과는 단순한 세포사멸에 의해서 일어나는 것이 시험물질에서 염증 매개물질 생성을 억제 한다는 것을 의미한다(Kim et al., 2011). 즉 대황목단피탕의 MPL 농도는 100 ㎍/ml로 설정하였으며, 100 ㎍/ml 이하의 농도에서 염증성 매개물질의 생성억제정도를 파악하여 세포독성이 없음을 확인하였다.

6. LPS 처치에 따른 세포독성

LPS는 염증성 매개물질의 분비를 활성시키는 대표적인 염증 유발물질이다(Radi et al., 1991). 본 실험에서 RAW 264.7 cell에 LPS를 단독으로 처치하였을 때 77.71%의 낮은 세포생존율을 나타내었다. 이것은 LPS로 인한 염증발생이 세포생존율에 영향을 주어 나타낸 결과로 보여진다(Higuchi et al., 1990). LPS와 대황목단피탕을 12.5, 25, 50, 100 ㎍/ml의 농도로 함께 처치할 경우 각각 93.97, 92.77, 91.45, 89.71%의 세포생존율을 보였으며 이 결과는 LPS만을 처치한 결과와 비교할 때 매우 증가함을 알 수 있었다(Fig. 2). 이는 화장품약리활성 검증을 위한 모링가 추출물에 대한 연구와 동일한 양상이다(Kim et al., 2018). LPS로 인해 유발되는 염증반응이 대황목단피탕에 의해 억제되어 염증반응으로 발생하는 세포사멸이 줄어든 것으로 보여지며, 실험군에서 세포생존율이 높으므로 이후 진행되는 실험의 결과에서는 유의미한 결과로 해석할 수 있다.

7. NO 생성 저해

본 연구에서는 LPS로 유도된 RAW 264.7 세포에서 대황목단피탕의 NO 생성 저해 활성을 확인하고자 하였다. NO는 정상적인 농도로 인체내에서 존재하면 세포의 신호전달과 대식 세포의 항균 활성, 감염 병원체의 억제 등의 다양한 효능이 있다(Hyun et al., 2015).

실험결과 대황목단피탕의 처치농도가 높아질수록 NO 생성 저해가 증가한 것으로 보여졌고, LPS 단독 처치군과 비교할 때 유의한 감소를 나타내었다(Fig. 3). 특히 100 ㎍/ml에서 24.62%의 NO 생성 저해율을 보였으며 12.5 ㎍/ml과 25 ㎍/ml을 효과를 비교했을 때 NO생성 저해율이 1.54%, 10.26%로 농도가 2배 증가했으나 억제율은 약 6.67% 증가한 것을 확인하였다. 이는 아토피, 노화, 문제성 피부 등에 효과적인 화장품 천연 소재로서 활용가능성을 확인하고자 하는 선행연구(Lee & Kim, 2023; Cho et al., 2023)들과 동일한 결과를 보여주었다.

IV. 결 론

본 연구에서는 대황목단피탕을 이용하여 천연화장품소재물로서의 적용가능성을 확인하기 위하여 항산화 평가와 RAW 264.7 cell을 통한 항염증실험을 실시하였다. 시험결과 ABTS+ radical scavenging activity와 Superoxide domutase(SOD)-like activity, DPPH에 대한 electron-donating ability를 통해 항산화 효능을 평가하였으며 모든 실험에서 농도의존적으로 항산화 효능이 증가됨을 확인하였다. 또한, RAW 264.7 cell에서 대황목단피탕은 100 ㎍/ml까지 세포 독성이 나타나지 않았으며, NO 생성저해율을 측정한 결과 100 ㎍/ml에서 24.62%의 발현 억제율을 보여 항염의 효과가 있음을 확인하였다. 이상의 결과를 종합해 볼 때 대황목단피당은 항산화 효과 및 항염 효과가 있음을 검증하였고 피부에 적용하기 위한 천연소재물로서의 가능성을 확인하였다. 본 연구 결과는 대황목단피탕의 연구의 기초자료가 사용할 수 있을 것으로 예상하고, 추후 화장품 천연물 관련 연구에 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 것으로 기대된다.